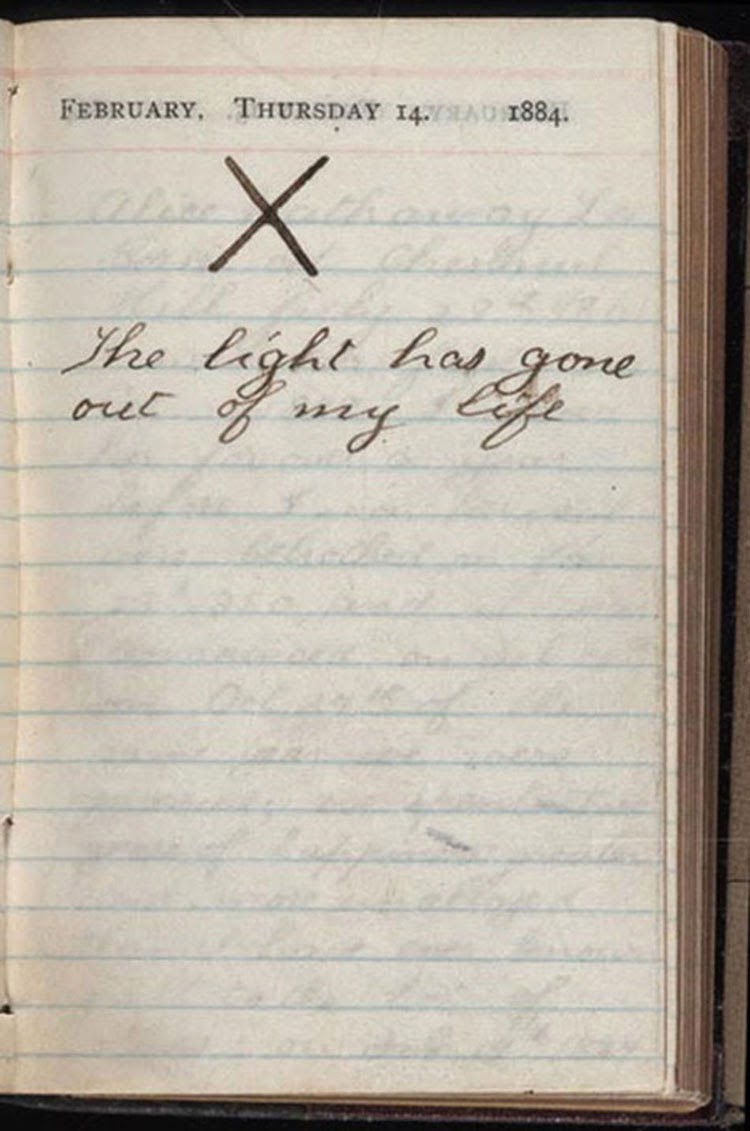

Theodore Roosevelt simply wrote an “X” above one striking sentence: “The light has gone out of my life”, 1884.

On February 14, 1884, Theodore Roosevelt received a terrible news, his wife and mother died within hours of one another in Roosevelt’s house in New York City.

His mother, age 50, succumbed to typhus, and his wife Alice died at the age of 22 giving birth to her namesake.

The following diary entries lovingly describe his courtship, wedding, happiness in marriage, and his grief over the death of his wife Alice.

In his ever-present pocket diary on February 14, 1884, Theodore Roosevelt simply wrote an “X” above one striking sentence: “The light has gone out of my life“.

Roosevelt had been called by telegram back to New York City from Albany where he was a New York State Assemblyman. The concern was his mother’s fading health. Alice had just given birth to a baby girl two days earlier.

But by the time Theodore reached his home at 6 West Fifty-seventh street, Alice’s condition had taken a serious downward turn. He was greeted at the door by his brother, Elliott, who ominously told him that “there is a curse on this house”.

And so it seemed. Roosevelt’s not yet 50-year-old mother, Mittie, was downstairs burning up with a fever from typhoid. And upstairs, his beloved Alice, scarcely able to recognize him was dying of undiagnosed Bright’s disease.

Alice died two days after their daughter was born from an undiagnosed case of kidney failure (in those days called Bright’s disease), which had been masked by the pregnancy.

His mother Mittie died of typhoid fever on the same day, at 3:00 am, some eleven hours earlier, in the same house.

His wife: Alice Hathaway Lee, President Theodore Roosevelt, his mother: Martha Stewart “Mittie” Bulloch.

Since he first cast his eyes upon Alice’s face in 1878, Theodore Roosevelt had filled pages of his diary by writing about her nearly as often as he thought about her.

He noted the simplest expressions, the smallest acts of recognition, the quietest smiles, the loudest silences, and every action that resulted in a memory that they could replay again-and-again in the future that they had planned together.

After his wife died, Roosevelt not only never spoke her name again but never allowed anyone else to speak her name in his presence.

That included their daughter, Alice Longworth Roosevelt, who never heard her father speak her mother’s name.

His belief was, and he told this to a friend who also lost his wife, that the pain had to be buried as deep inside as possible or it would destroy you. This is the opposite of the current opinion that feelings should be shared.

In a short, privately published tribute to Alice, Roosevelt wrote:

She was beautiful in face and form, and lovelier still in spirit; As a flower she grew, and as a fair young flower she died.

Her life had been always in the sunshine; there had never come to her a single sorrow; and none ever knew her who did not love and revere her for the bright, sunny temper and her saintly unselfishness.

Fair, pure, and joyous as a maiden; loving, tender, and happy. As a young wife; when she had just become a mother, when her life seemed to be just begun, and when the years seemed so bright before her—then, by a strange and terrible fate, death came to her. And when my heart’s dearest died, the light went from my life forever.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress).