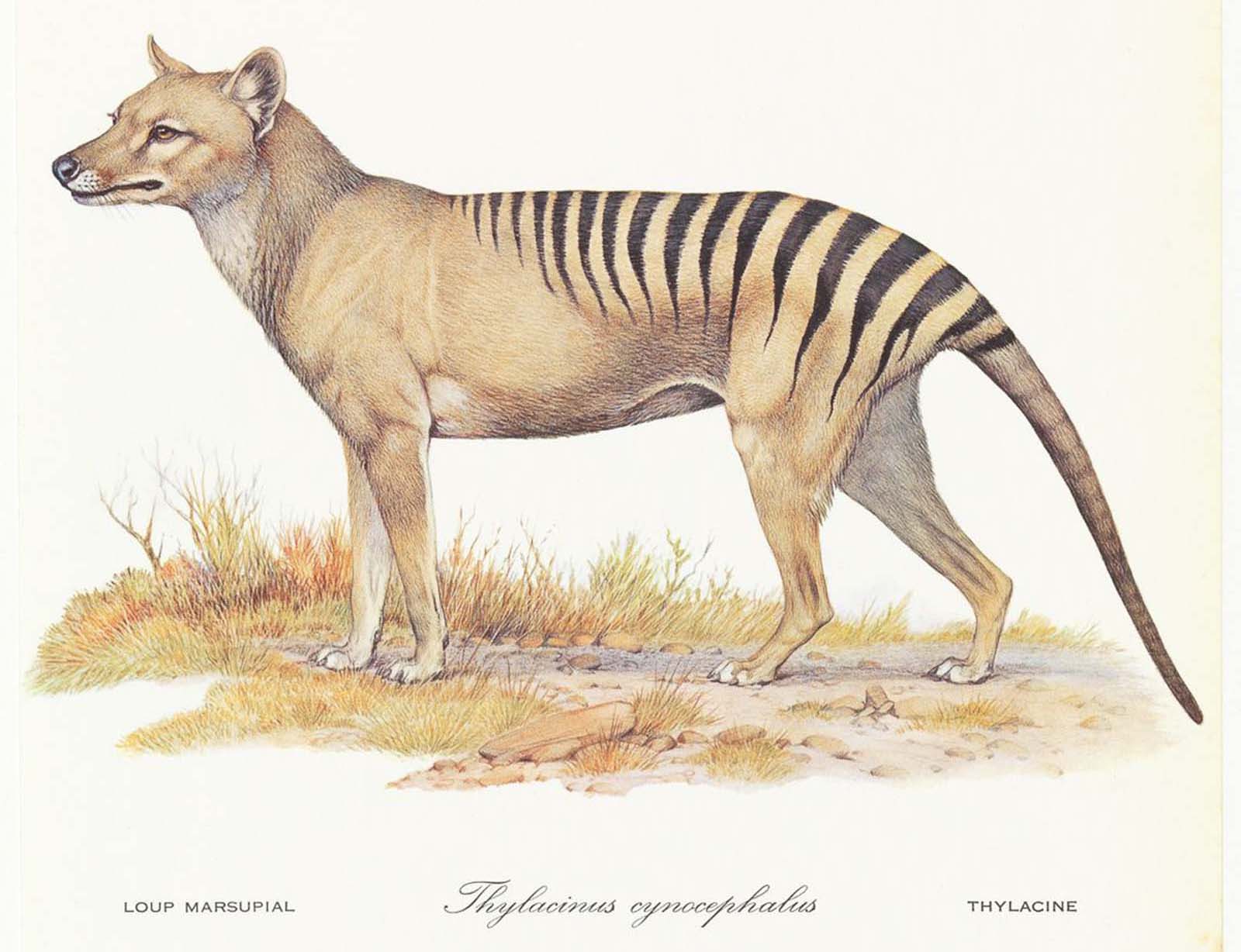

The thylacine, most commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger because of its striped lower back or the Tasmanian wolf because of its canid-like characteristics, was one of the largest carnivorous marsupials.

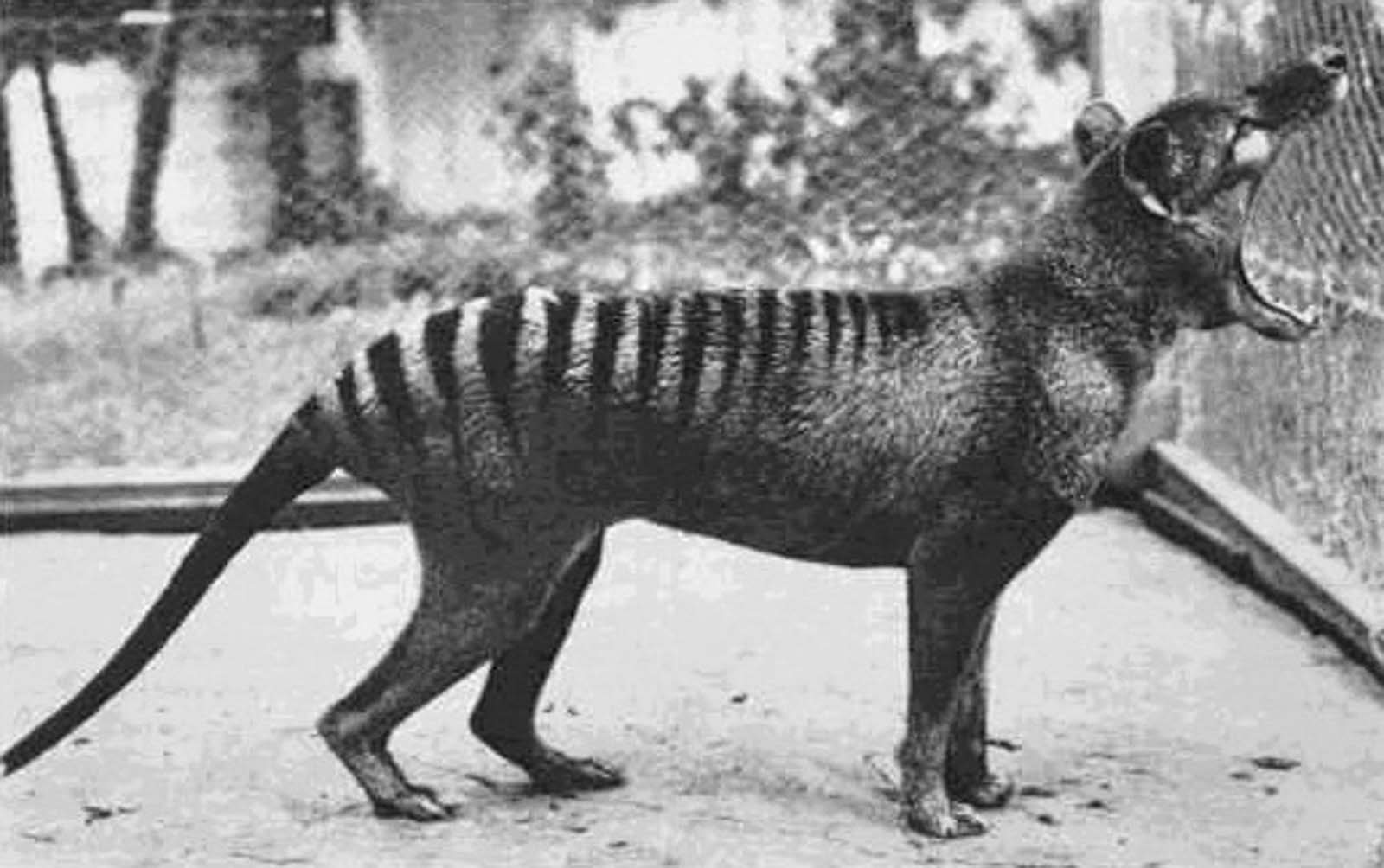

The thylacine was relatively shy and nocturnal, with the general appearance of a medium-to-large-size dog, except for its stiff tail and abdominal pouch similar to a kangaroo’s, and dark transverse stripes that radiated from the top of its back, reminiscent of a tiger.

The thylacine was a formidable apex predator, though exactly how large its prey animals were is disputed. Originally, the thylacine had been found on the Australian mainland and New Guinea and was confined to Tasmania only in historic times. Competition with the dingo probably led to its disappearance from the mainland.

It was native to Tasmania, New Guinea, and the Australian mainland.

The first notes of a thylacine were written during the Bruni d’Entrecasteaux’s expedition to Oceania in 1792, describing “a quadruped, the size of a large dog…of a white colour marked with black, [which] had the appearance of a wild beast”.

The first specimen was killed by Europeans in March 1805 and immediately the difficult relationship between colonists and the predator became evident.

Considered a threat to sheep, the major resource of the economy of the colony, the Tasmanian tiger was fiercely hunted. As early as 1830 bounty systems for the thylacine had been established, with farm owners pooling money to pay for skins.

The last known live animal was captured in 1933 in Tasmania.

In 1888 the Tasmanian Government also introduced a bounty of £1 per full-grown animal and 10 shillings per juvenile animal destroyed.

The program extended until 1909 and resulted in the awarding of more than 2180 bounties. It is estimated that at least 3500 thylacines were killed through human hunting between 1830 and the 1920s.

It was rare by 1914, and the last known living specimen died in a private zoo in Hobart in 1936; its disappearance from the wild came perhaps two years later.

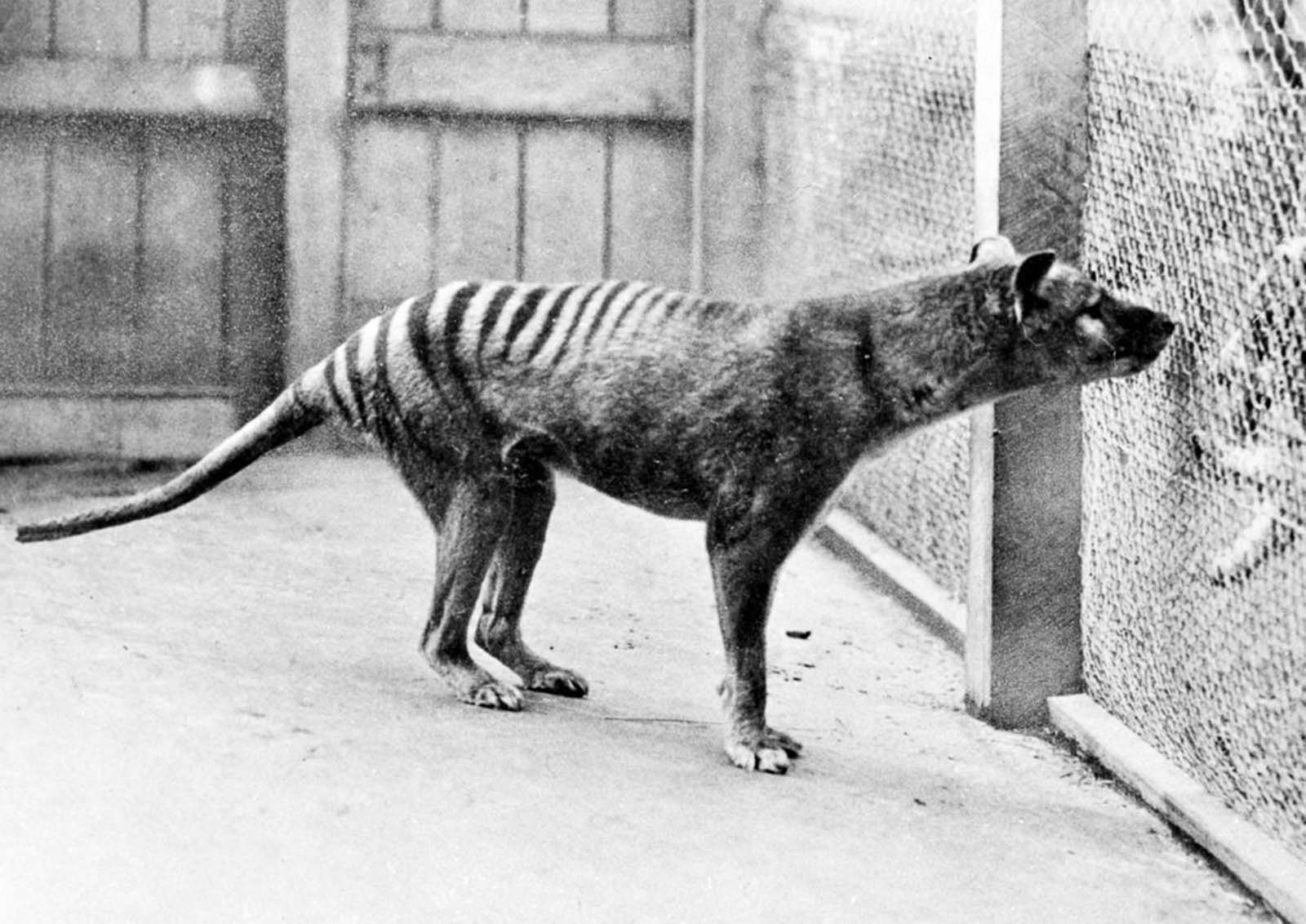

One of the last thylacines in captivity at the Hobart Zoo. 1933.

The thylacine was probably almost a rare species in the early years of the European settlement and this confined population was ulterior weakened by the persecution as “sheep-killer”. It is also possible that during this “bottleneck phase” a final epidemic decimated the remaining animals.

The last captive thylacine, later referred to as “Benjamin”, was trapped in the Florentine Valley by Elias Churchill in 1933, and sent to the Hobart Zoo where it lived for three years. The thylacine died on 7 September 1936.

The thylacine had become extinct on the Australian mainland before British settlement of the continent, but it survived on the island of Tasmania along with several other endemic species, including the Tasmanian devil.

It is believed to have died as the result of neglect—locked out of its sheltered sleeping quarters, it was exposed to a rare occurrence of extreme Tasmanian weather: extreme heat during the day and freezing temperatures at night.

This thylacine features in the last known motion picture footage of a living specimen: 62 seconds of black-and-white footage showing the thylacine in its enclosure in a clip taken in 1933, by naturalist David Fleay.

In the film footage, the thylacine is seen seated, walking around the perimeter of its enclosure, yawning, sniffing the air, scratching itself (in the same manner as a dog), and lying down.

A Tasmanian hunter with a recently killed thylacine. 1925.

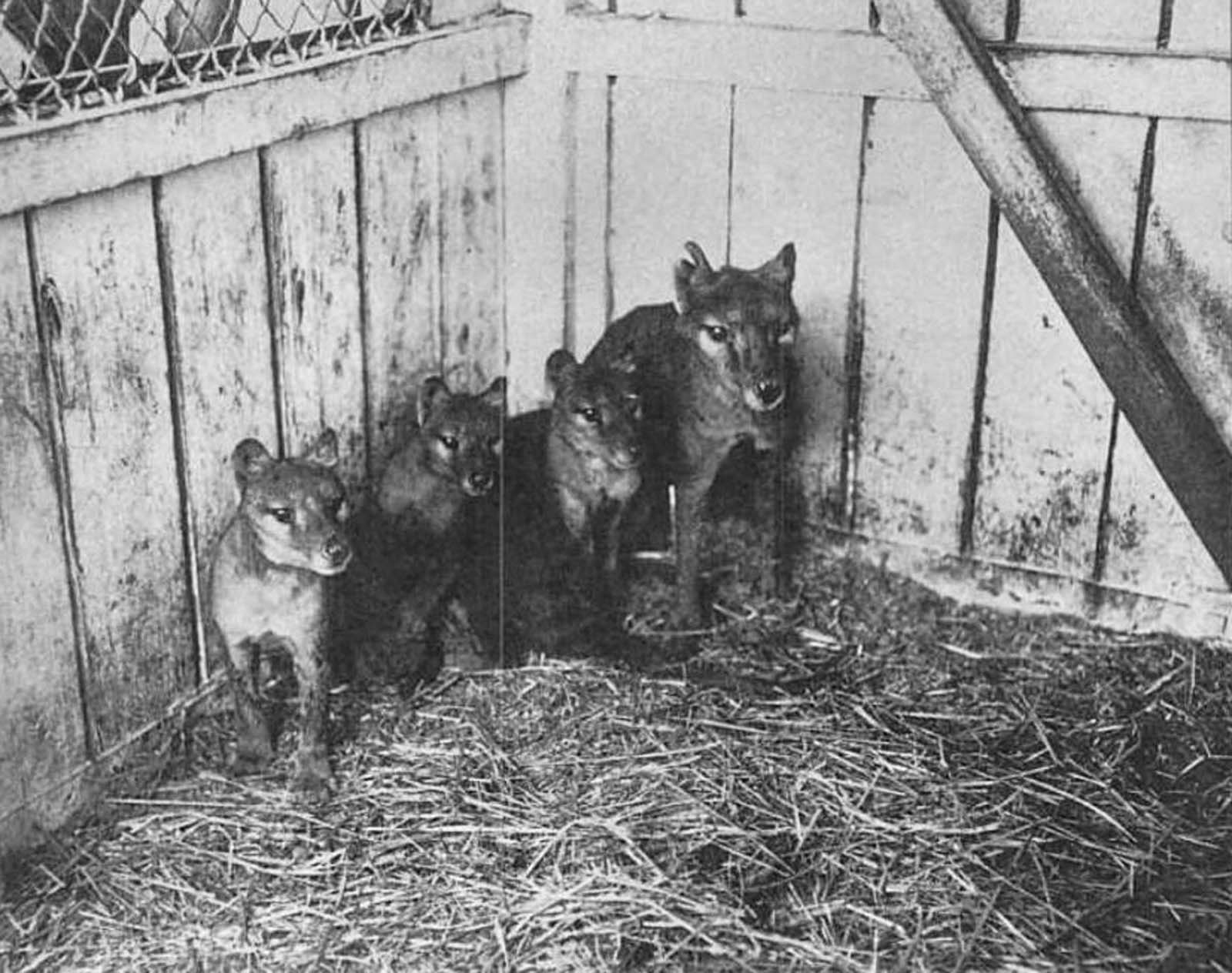

An adult thylacine and three juveniles at the Hobart Zoo. 1909.

Intensive hunting encouraged by bounties is generally blamed for its extinction, but other contributing factors may have been disease, the introduction of dogs, and human encroachment into its habitat.

A family of thylacines at the Hobart Zoo. 1910.

Thylacine.

A preserved body of a thylacine at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. 2005.

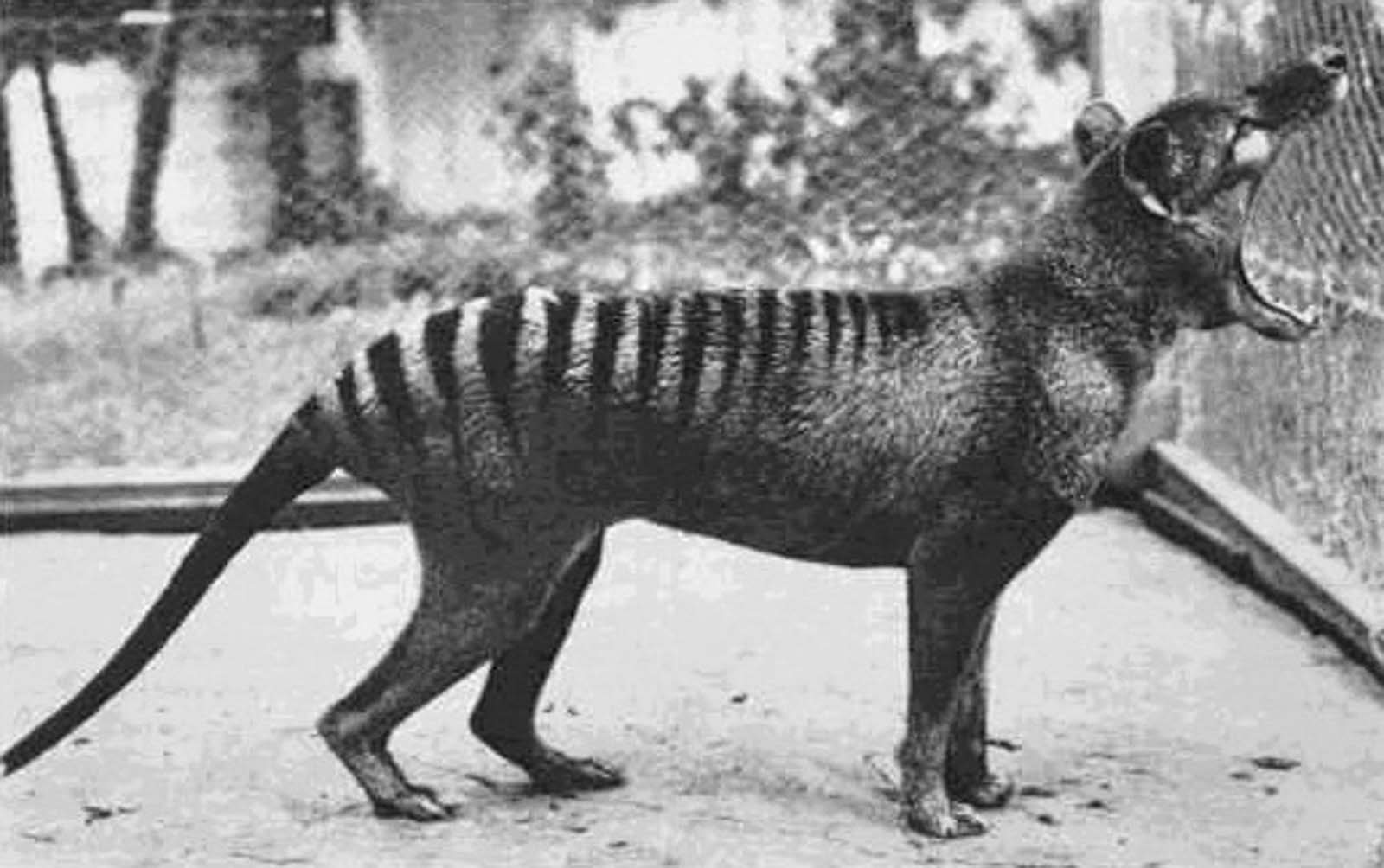

The last living thylacine in captivity yawns at the Hobart Zoo. Thylacines were capable of opening their jaws as wide as 80 degrees. 1933.

(Photo credit: Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).