The final photographs taken aboard Japan Airlines Flight 123 remain haunting reminders of the moments before tragedy struck.

The final photographs taken aboard Japan Airlines Flight 123 remain haunting reminders of the moments before tragedy struck.

On August 12, 1985, the Boeing 747 crashed into a remote mountain ridge in Japan, killing 520 of the 524 people on board. To this day, it stands as the deadliest single-aircraft disaster in aviation history.

Among the images recovered, two were taken during an ordinary climb over Tokyo, and one was captured less than a minute before impact, preserving a chilling glimpse of life inside the doomed aircraft.

The plane in its take-off roll above Tokyo. (Photo taken by a passenger).

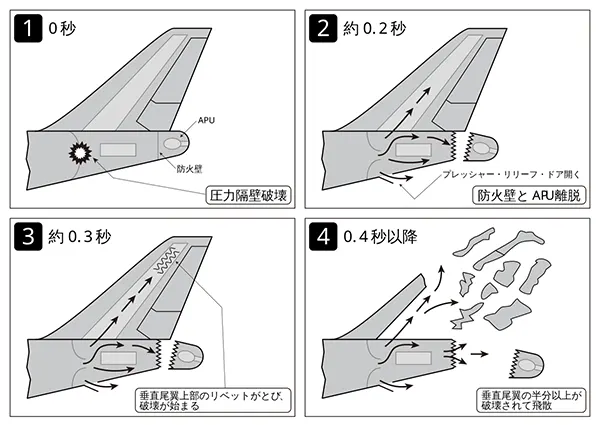

Sequence of Events: The Accident

At 6:12 p.m., Flight 123 lifted off from Haneda. Just twelve minutes later, climbing through 23,900 feet at a speed of 300 knots, disaster struck.

A loud explosion reverberated through the cabin as the rear pressure bulkhead ruptured, unleashing a rapid decompression that tore through the tail of the aircraft.

The vertical fin, a five-meter section of the tailcone, and the auxiliary power unit were ripped away in an instant.

Another image taken from inside the plane.

The sudden structural failure left the crew with almost no control. The decompression damaged all four hydraulic systems, rendering the ailerons, elevators, and yaw damper inoperative.

The pilots, now fighting to keep the aircraft in the sky, could only attempt control through engine thrust. What followed was 32 minutes of unimaginable struggle.

The 747 began oscillating in wide, violent motions known as “dutch rolls” and phugoid cycles—erratic climbs and dives that alternated between dangerously low airspeeds and steep nose-up pitches.

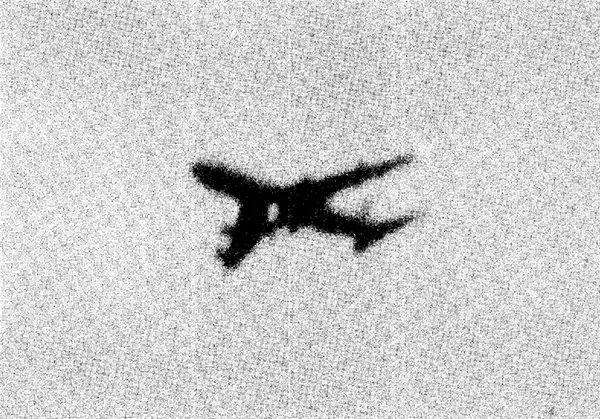

A photo taken by a passenger inside the cabin of flight 123 after the explosive decompression. Everyone in this photo, including the cameraperson, perished in the crash.

At one point, the jet descended to 6,600 feet at only 108 knots, then pitched up nearly 39 degrees and climbed back to 13,400 feet before losing control again.

Despite the crew’s extraordinary efforts, the aircraft continued to stagger through the sky, its fate sealed by the loss of its critical systems.

At 6:56 p.m., after a half-hour of desperate attempts to control the aircraft, Flight 123 brushed against a ridge before slamming into Mount Takamagahara in Gunma Prefecture.

The aircraft broke apart and erupted into flames at an elevation of 5,135 feet. The violence of the impact and the remote location ensured that survival would be rare.

JA8119, the aircraft involved in the accident, pictured in 1984.

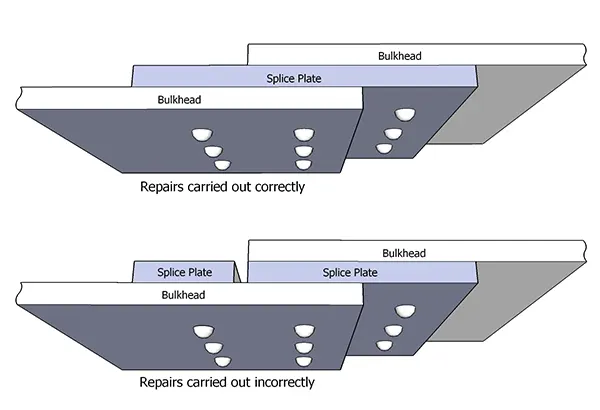

The Fatal Flaw Rooted in Previous Repair

The seeds of this tragedy were sown seven years earlier. On June 2, 1978, the same aircraft—tail number JA8119—was involved in a tailstrike incident while landing in Osaka.

The mishap severely damaged the rear pressure bulkhead, a crucial structure that maintains cabin pressurization. Boeing repaired the aircraft, but a critical mistake was made during the process.

Instead of following approved repair procedures that required a single continuous splice plate with three rows of rivets, Boeing technicians installed two shorter plates side by side.

Instead of following approved repair procedures that required a single continuous splice plate with three rows of rivets, Boeing technicians installed two shorter plates side by side.

This weakened the structure, reducing its resistance to fatigue. Over the next seven years and more than 12,000 pressurization cycles, cracks slowly spread until the bulkhead could no longer withstand the stress.

When it finally gave way on that August evening in 1985, it set in motion the disaster that followed.

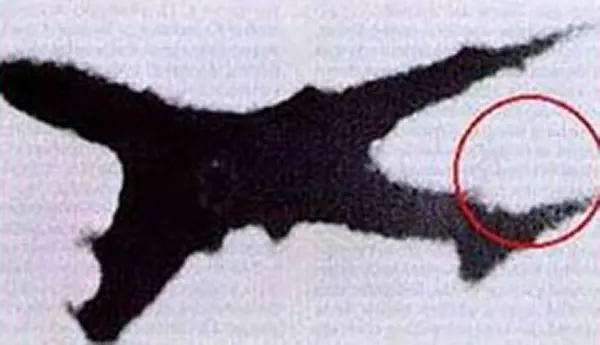

Here we can see the vertical stabilizer largely missing.

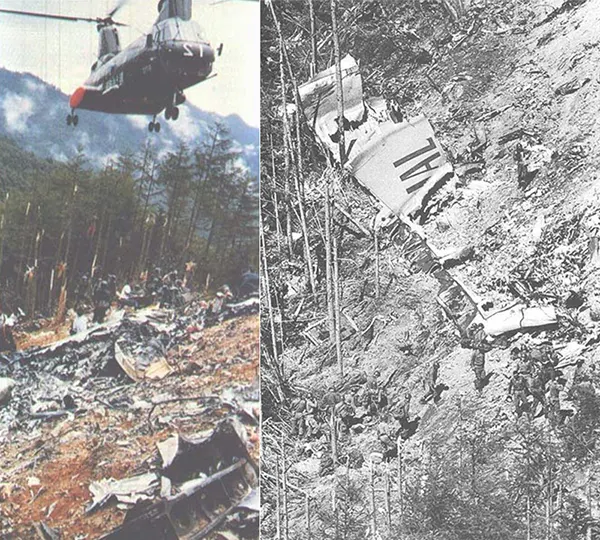

The Crash Site and Rescue Operation

The crash site, deep in the mountains of Gunma Prefecture, was difficult to reach. Rescue teams were delayed, and though some passengers survived the initial impact, many succumbed overnight to injuries, shock, or exposure.

Medical examiners later confirmed that earlier rescue efforts could have saved additional lives. Only four people survived.

One doctor said, “If the discovery had come 10 hours earlier, we could have found more survivors.”

Vertical stabilizer decompression and separation sequence (in Japanese).

One of the four survivors, off-duty Japan Air Lines flight purser Yumi Ochiai recounted from her hospital bed that she recalled bright lights and the sound of helicopter rotors shortly after she awoke amid the wreckage, and while she could hear screaming and moaning from other survivors, these sounds gradually died away during the night.

The rescue response itself became a point of controversy. A U.S. Air Force navigator stationed at Yokota Air Base later revealed that American forces had tracked the distress calls and prepared a search-and-rescue mission, only for it to be called off at the request of Japanese authorities.

Correct (top) and incorrect (bottom) splice plate installations

A U.S. Air Force C-130 spotted the crash site within 20 minutes of impact, while daylight still remained, and relayed the coordinates.

A helicopter was dispatched, but Japanese officials declined assistance, leaving the wreckage undiscovered until nightfall by a Japanese Self-Defense Forces helicopter.

Rescue teams did not reach the site until the following morning, by which time it was too late for many who might otherwise have survived.

The damaged aircraft photographed over Okutama approximately 6 minutes before the crash with the vertical stabilizer largely missing.

Investigation and Findings

The Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission of Japan, supported by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board, conducted an exhaustive inquiry.

Their final report, released in June 1987, placed the blame squarely on the faulty repair made by Boeing after the 1978 tailstrike.

The incorrect use of two splice plates instead of one had compromised the strength of the rear pressure bulkhead.

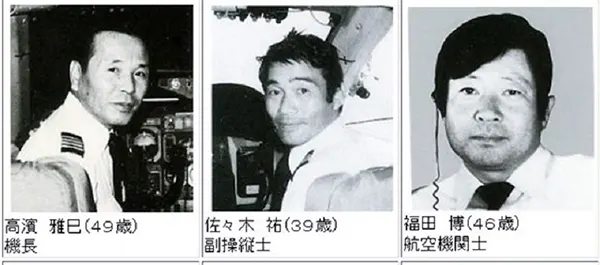

The pilots.

The subsequent repair of the bulkhead did not conform to Boeing’s approved repair methods. For reinforcing a damaged bulkhead, Boeing’s repair procedure calls for one continuous splice plate with three rows of rivets.

The Boeing repair technicians, however, had used two splice plates parallel to the stress crack.

Cutting the plate in this manner negated the effectiveness of the row of rivets, reducing the part’s resistance to fatigue cracking to about 70% of that for a correct repair.

In this aerial photo, the tail section can be seen in the bottom of the ravine on the left, where it rolled after the crash. This is where the survivors were found.

The post-repair inspection by JAL did not discover the defect, as it was covered by overlapping plates.

While it was strong enough to withstand operations for several years, investigators calculated that it would fail after roughly 11,000 cycles of pressurization. By the time of the accident, the aircraft had completed 12,318 flights, exceeding that threshold.

The defect went undetected in subsequent inspections because it was hidden beneath overlapping repair plates. When it finally failed, it caused the decompression and structural collapse that doomed the aircraft.

A survivor is shown being hoisted into a helicopter in this photo taken from NHK’s broadcast.

Rescuers lift Keiko Kawakami into a helicopter for immediate transportation to hospital.

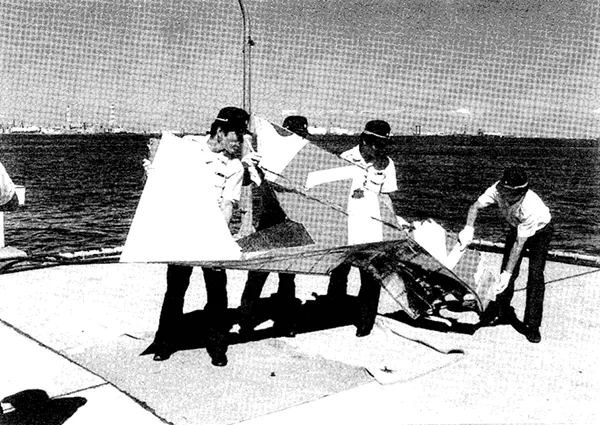

Parts of the vertical tail fin being recovered from the sea.

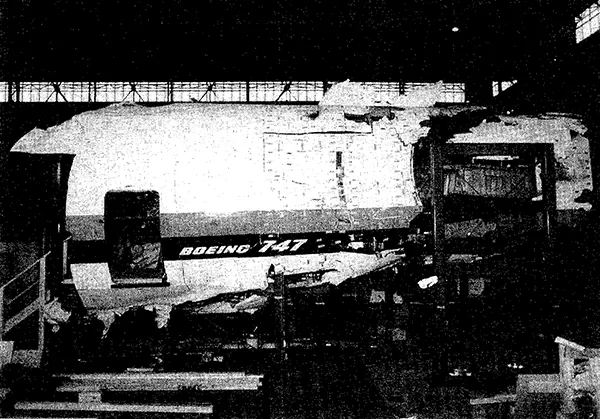

Reconstruction of the left side of the fuselage.

Rescuers at the crash site.

Flight 123 accident monument in Fujioka.

In 2009, stairs with a handrail were installed to facilitate visitors’ access to the crash site.

On August 12, 2010, for the 25th anniversary of the accident, Japan Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism Minister Seiji Maehara visited the site to remember the victims.

Families of the victims, together with local volunteer groups, hold an annual memorial gathering every August 12 near the crash site in Gunma Prefecture.

Japan Airlines Flight 123 Memorial at Ueno, Gunma.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / RHP / Flickr / Britannica / WSJ / BBC).