At the far edges of the nineteenth-century world, the Arctic stood as both a lived homeland and a testing ground for human ambition.

At the far edges of the nineteenth-century world, the Arctic stood as both a lived homeland and a testing ground for human ambition.

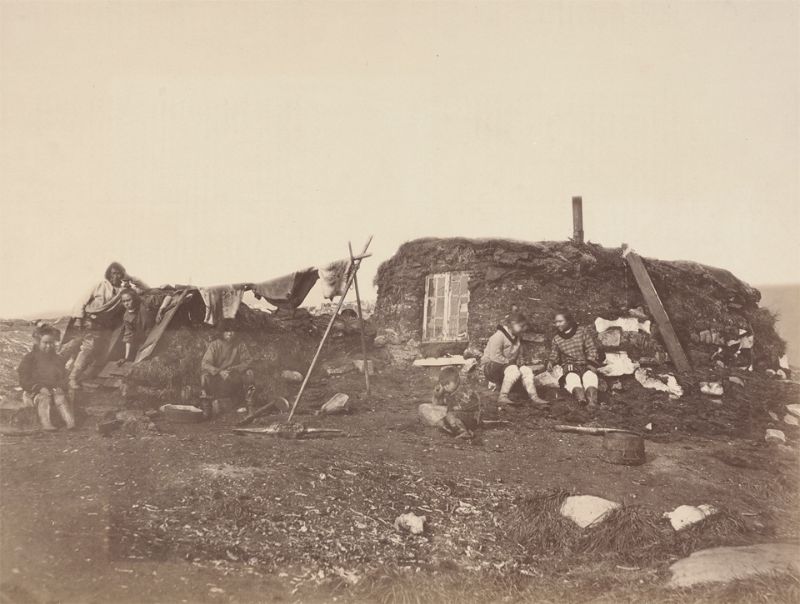

Long before explorers and photographers arrived with cameras and scientific instruments, Indigenous peoples such as the Inuit, Sámi, and Chukchi had built strong societies across the polar regions.

Their lives were shaped by seasonal movement, hunting and fishing, and an intimate understanding of ice, weather, and animal behavior.

Families traveled by sled and skin boat, clothing was sewn from fur and hide for survival rather than fashion, and oral traditions preserved history in a land where written records were rare.

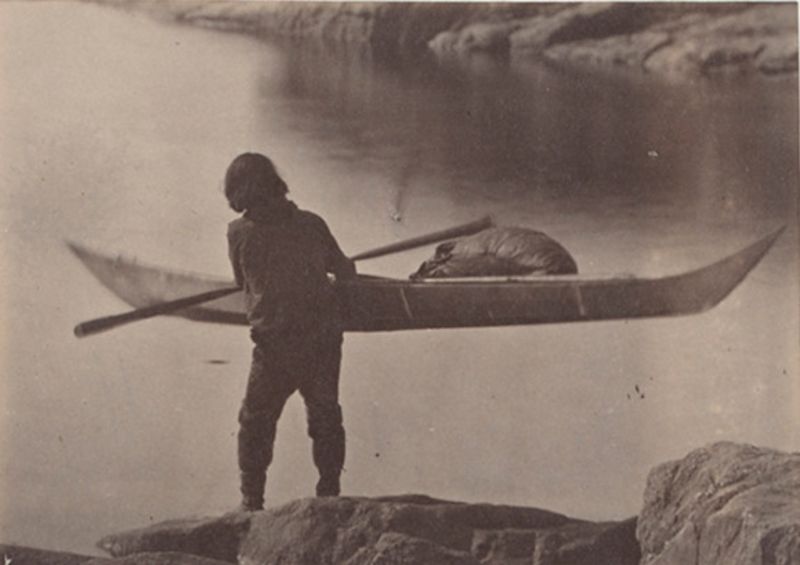

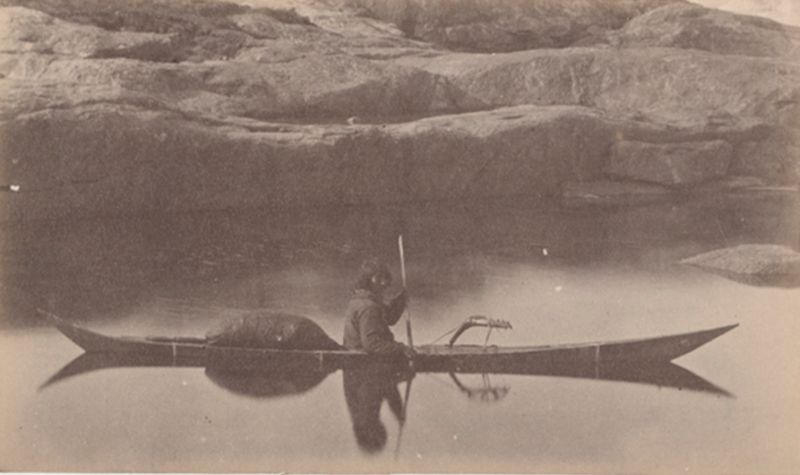

An Esquimaux getting ready for a seal hunt.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these communities found themselves increasingly observed, documented, and sometimes disrupted by outsiders who viewed the Arctic as both a scientific frontier and a symbol of endurance

Some of the most striking visual records from this era come from the work of William Bradford, whose monumental volume The Arctic Regions was published in London in 1873.

Bradford, born in 1823 and best known as a painter and photographer, set out to capture Greenland and its people at a time when photography itself was still a demanding and uncertain process.

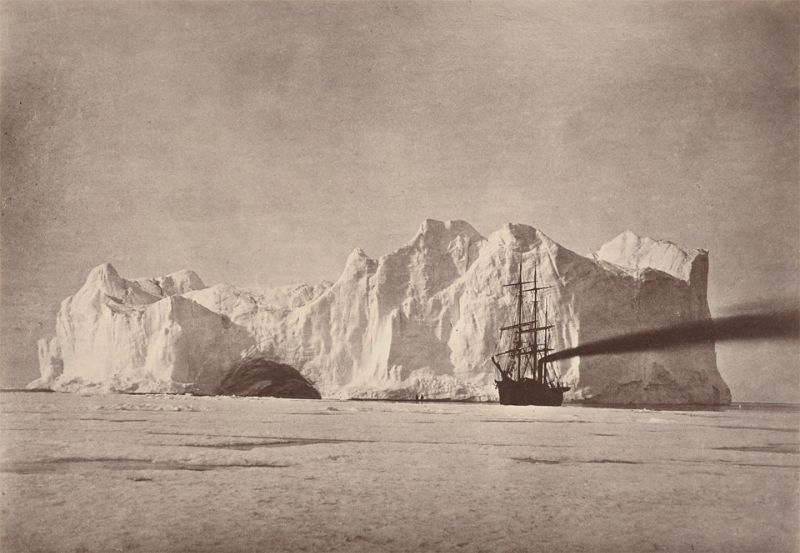

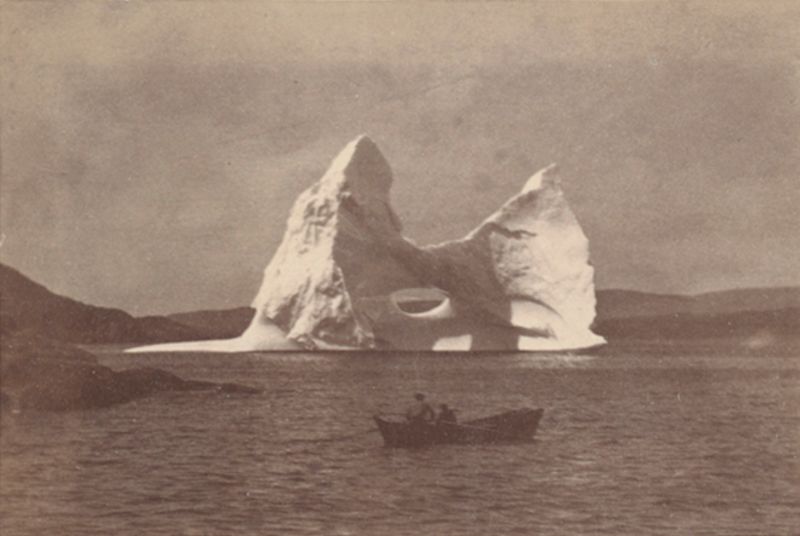

Beautiful forms in varied shapes which the berg assumed.

His project received significant backing, including sponsorship from Queen Victoria, and was produced in an estimated print run of just 300 copies.

Today, surviving volumes are rare, with several preserved in institutions in and around New Bedford, Massachusetts, including the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Bradford’s images do more than illustrate landscapes; they freeze moments of daily life, whaling culture, icebound ships, and Arctic settlements at a time when the region was beginning to draw sustained global attention.

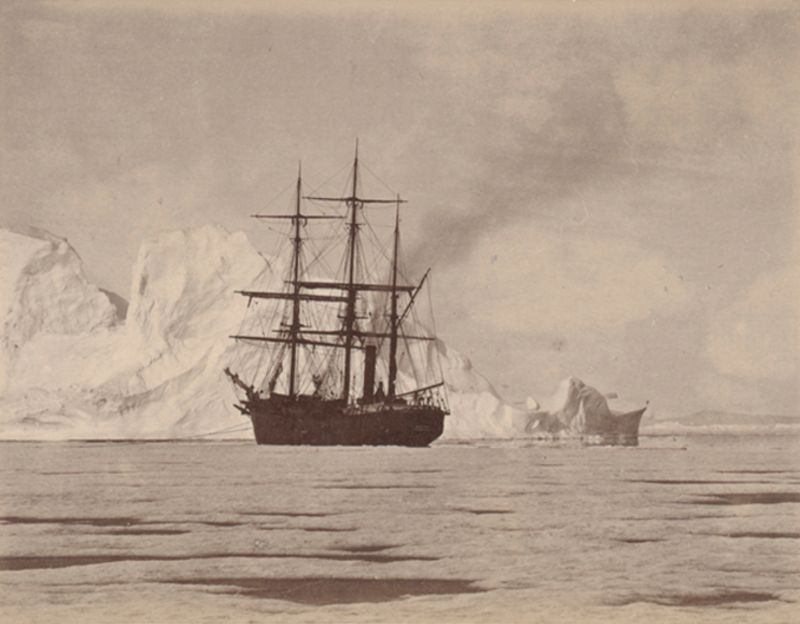

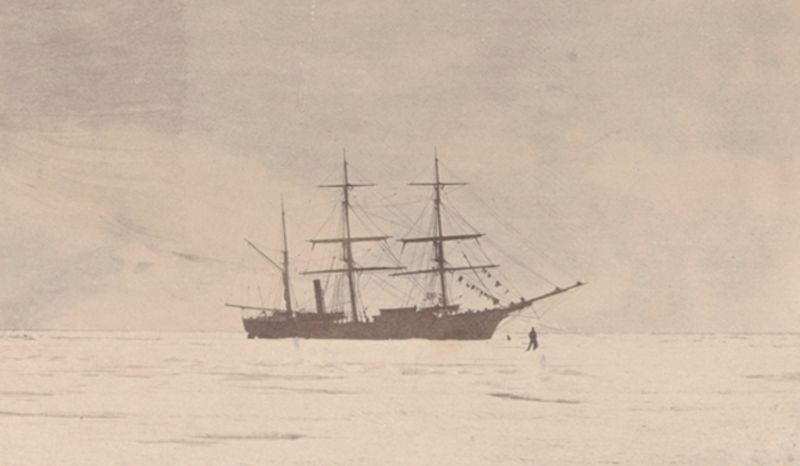

Between the iceberg and field ice. The “Panther” firing up to escape being forced on to the berg.

European contact with the Arctic was not new in the nineteenth century. The earliest known outsiders to reach these northern lands were the Vikings, who settled in Greenland around the tenth century and maintained communities there for roughly five hundred years.

These Norse colonies eventually vanished, likely due to a combination of climate shifts, isolation, and economic decline.

For centuries afterward, Arctic exploration remained sporadic and dangerous, limited by technology and incomplete knowledge of polar conditions.

Hunting by steam in Melville Bay.

Interest intensified during the sixteenth century, when European powers began to see the Arctic as a possible gateway to new trade routes.

The promise of a northern passage linking Europe and Asia drove expeditions into largely unmapped waters.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, explorers such as Henry Hudson of England, Willem Barents of the Netherlands, and John Ross of the British Royal Navy ventured north in search of navigable seas.

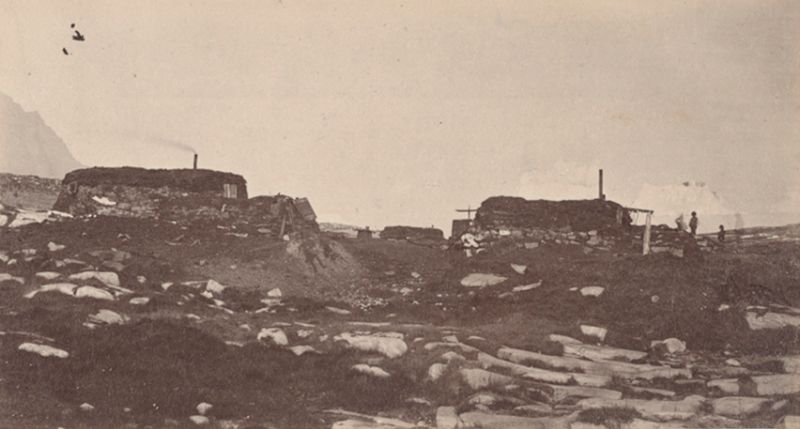

Esac’s house on Iglor at the right.

By the nineteenth century, Arctic exploration increasingly shifted from commercial ambition to scientific inquiry.

Expeditions were now organized to study geography, magnetism, ocean currents, and climate, often under the leadership of trained navigators or scientists.

Sir John Franklin became one of the most famous and tragic figures of this era. His final expedition, launched in 1845 to chart the Northwest Passage, ended with the loss of all 129 men.

The mystery surrounding their fate haunted the Victorian public and underscored the Arctic’s lethal unpredictability.

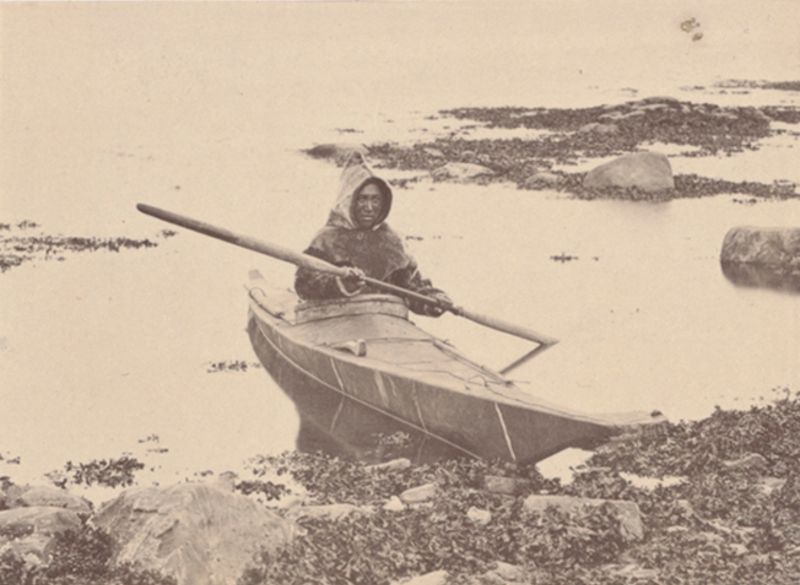

Esquimaux carrying his kayak to the water to start on hunt.

Later in the century, the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen brought a new level of scientific rigor to polar exploration.

In 1893, he embarked on a bold experiment aboard the specially designed ship Fram. Rather than fighting the ice, Nansen intentionally allowed his vessel to become frozen into it, hoping to drift across the Arctic Ocean and gather data on currents and ice movement.

The ship’s rounded hull was engineered to rise with the pressure of the ice rather than be crushed, a revolutionary design for its time. During this expedition, Nansen reached a latitude of 85°56′ north, closer to the North Pole than anyone before him.

Esquimaux igloe or winter hut, made of turf and stones.

The Fram expedition transformed understanding of the Arctic. Nansen demonstrated that there was no large undiscovered landmass north of Eurasia and confirmed that the Arctic Ocean reached depths exceeding 3,000 meters.

His observations also revealed that warmer Atlantic waters, carried by a branch of the Gulf Stream, flowed beneath the Arctic ice as a deep current.

These findings laid the groundwork for modern theories of ice drift and polar oceanography.

Esquimaux in his kayak or skin boat.

As the turn of the twentieth century approached, the race to reach the North Pole captured public imagination.

American explorer Frederick Cook claimed in 1908 that he had succeeded, but his account quickly came under scrutiny.

Critics pointed to vague descriptions, mathematical inconsistencies, and testimony from the Inuit who accompanied him, who later stated that they never lost sight of Greenland’s mountains. Cook’s claim was widely discredited.

Esquimaux in his kayak ready for seal-hunting.

Robert Peary, another American explorer, followed with his own assertion in 1909. Traveling with Matthew Henson and a team of Inuit companions, Peary declared that he had reached the Pole.

Yet his navigational methods were flawed, as he lacked reliable means to calculate longitude.

Subsequent analyses of his logbooks suggest that he fell short by several dozen kilometers. Despite these doubts, Peary’s claim dominated public perception for decades.

Esquimaux landing in his kayak, showing the way they often take out their wives for a short call.

Technological advances soon shifted exploration from sleds and ships to the air. In 1926, Richard E. Byrd announced that he had flown over the North Pole.

This claim, too, was later questioned. Reports from his pilot, Floyd Bennett, and discrepancies in flight timing suggested the aircraft could not have completed the journey as described. Historians now widely regard Byrd’s claim as unlikely.

Esquimaux mother and her fair-haired daughter.

The first widely accepted crossing of the North Pole came later that same year, when Roald Amundsen traveled over it aboard the airship Norge, accompanied by Italian engineer Umberto Nobile.

Amundsen was already celebrated for reaching the South Pole in 1911 and stood apart for his meticulous planning and respect for Indigenous knowledge.

His Arctic flight marked the close of an era defined by perilous trial and error.

Esquimaux toupek or skin tent.

The photographs from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries capture this transitional moment.

They show a region where Indigenous traditions endured alongside foreign ships, scientific camps, and ambitious explorers.

Seen through William Bradford’s lens and those who followed, the Arctic of this period emerges not as an empty wasteland, but as a complex human landscape shaped by survival, curiosity, and the relentless pull of the unknown.

Esquimaux toupek, or skin tent, used for camping out when making their journeys along the coast.

Esquimaux wide awake.

Esquimaux women, showing the manner in which they often carry their children on their backs in their hoods.

Group of Esquimaux women and children.

Hans, his wife and children.

Iceberg, showing the action of the water washing and wearing it into its present shape.

In an open lead between the floe and the iceberg.

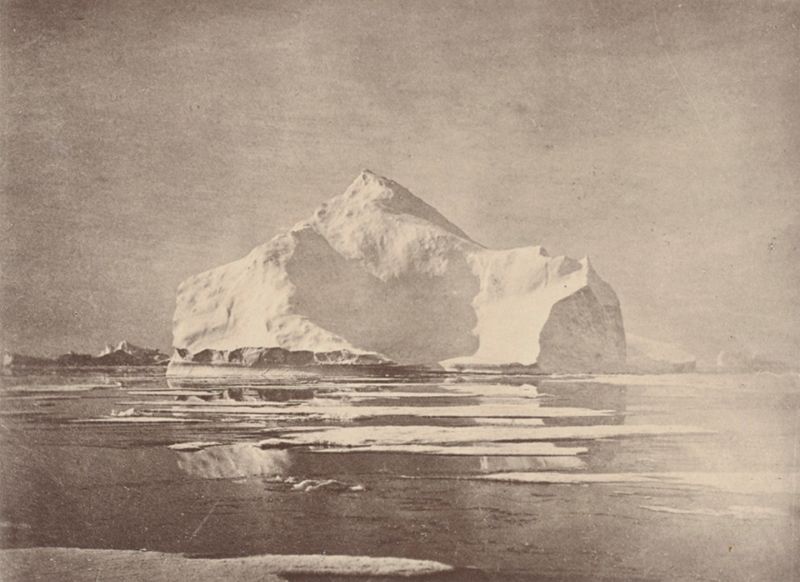

Instantaneous view of iceberg on our way north.

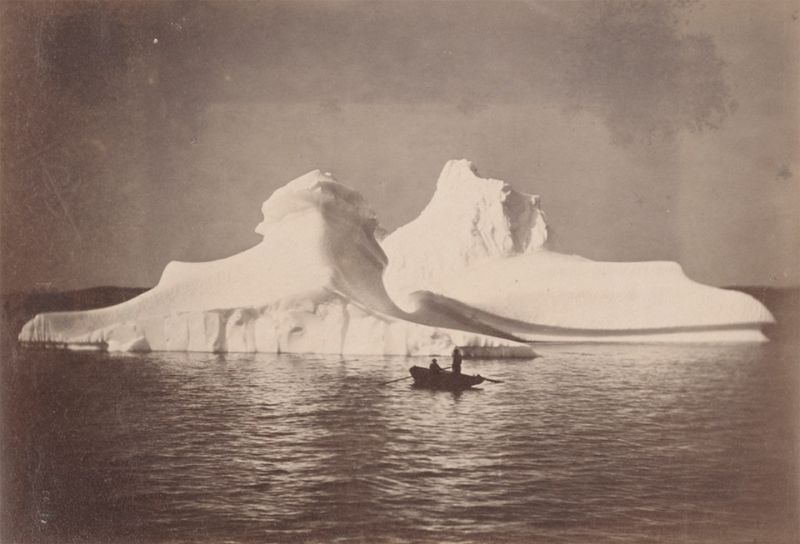

Instantaneous view of icebergs which, from their similarity and beauty, we named the twins.

Jansen and his family.

Looking down from Karsut Fjord.

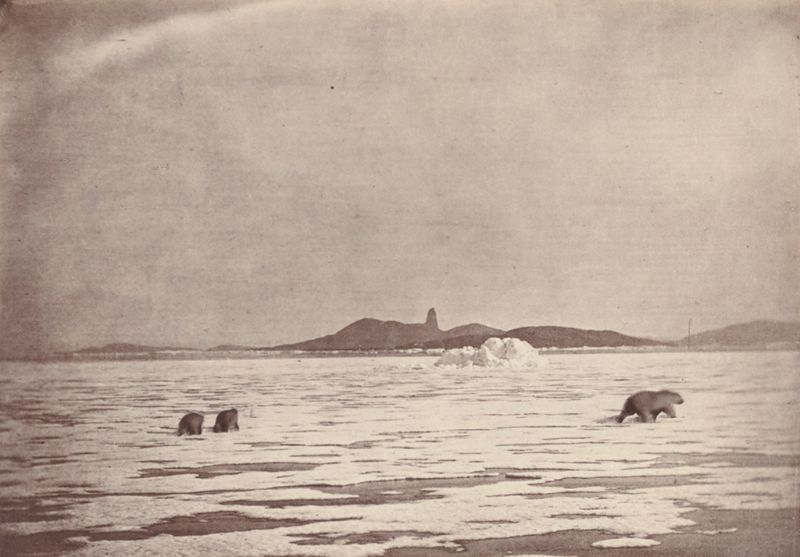

Nearer view of the polar bears.

Patiently waited and quietly hoped for the ice to open.

Philip and his family.

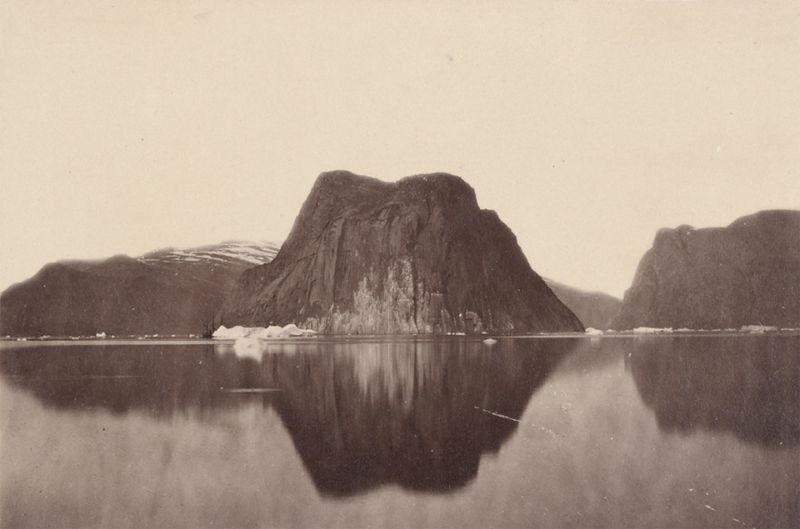

Sandstone Rock at the entrance of Karsut Fjord.

Sophy and her sister, Marea.

The “Panther” made fast to the floe in Melville Bay, between the icebergs and field ice.

The “Panther” fast in the field-ice in Melville Bay as far as the eye could see it was a vast unbroken sea of ice.

The “Panther” moored to the heavy hummock ice.

The “Panther” trying to force a passage through the floe.

The cliffs on the opposite side of the harbour of Godhaven, three hundred feet high.

The farthest point reached.

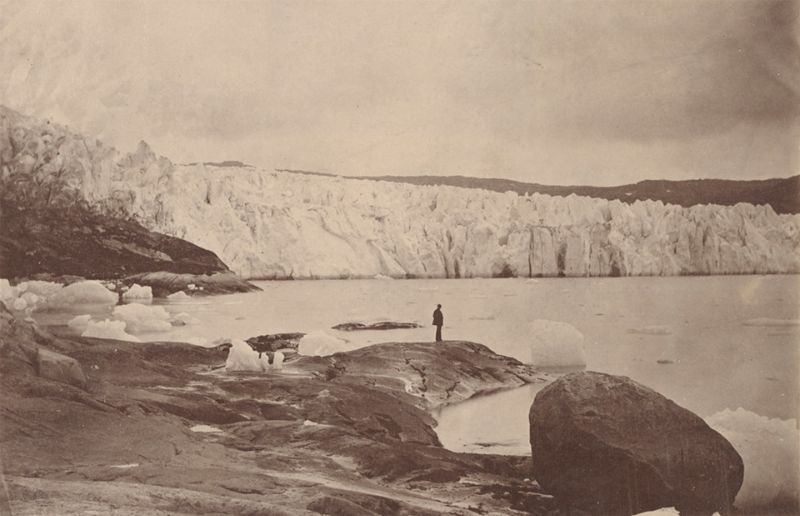

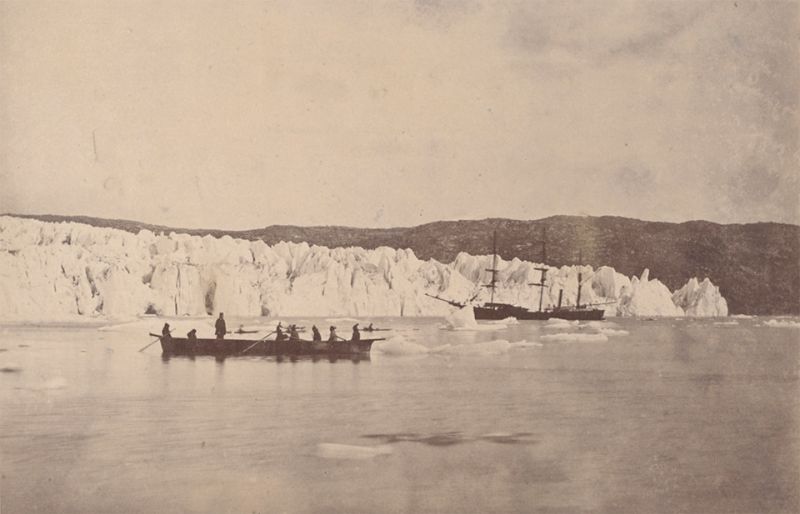

The glacier as seen forcing itself down over the land and into the waters of the fjord.

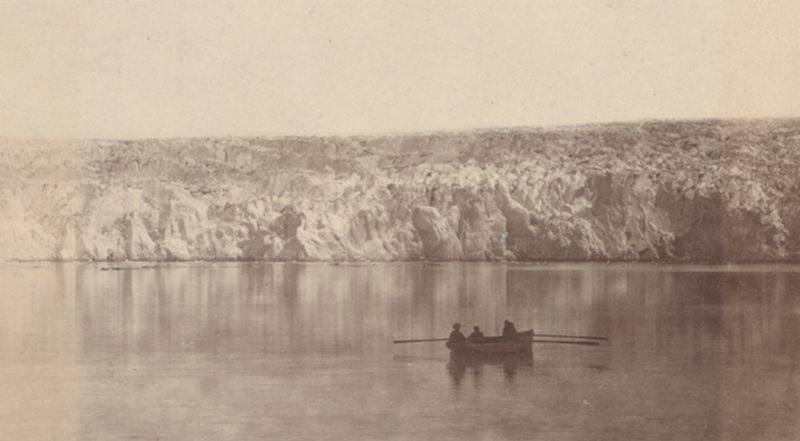

The glacier as seen when sailing up the fjord, showing its wall or front, and its top looking inland.

The house nearest the North Pole under the midnight sun.

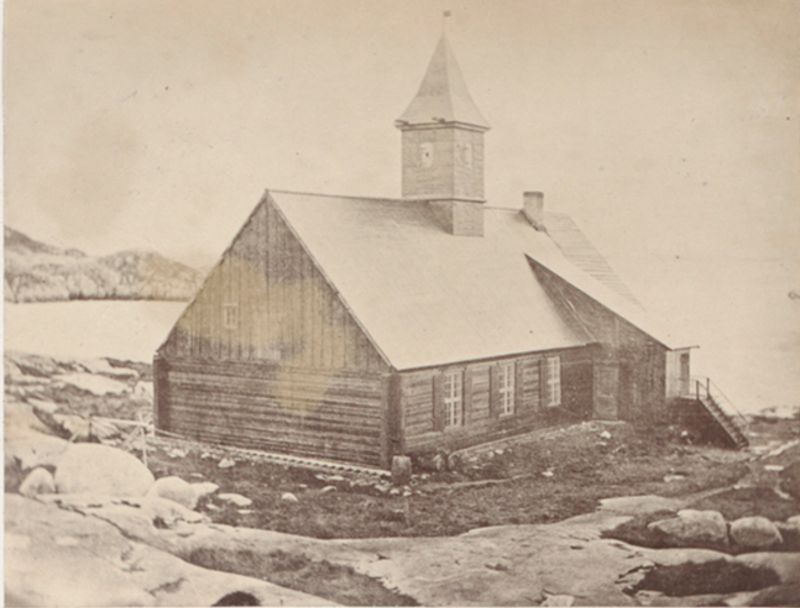

The Lutheran church at Jacobshaven, one of the finest in Greenland.

The middle pack of Melville Bay, with a group of stranded bergs.

The midnight sun in Melville Bay.

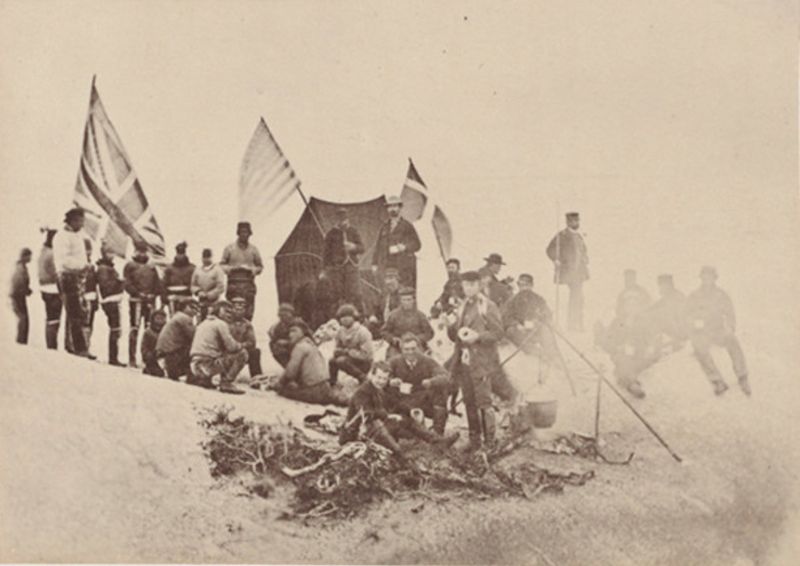

The party in camp on the top of the glacier.

The solitude of Melville Bay.

The steamer taking soundings in front of the glacier.

The steamer, in an open lead, moored to the edge of the ice field.

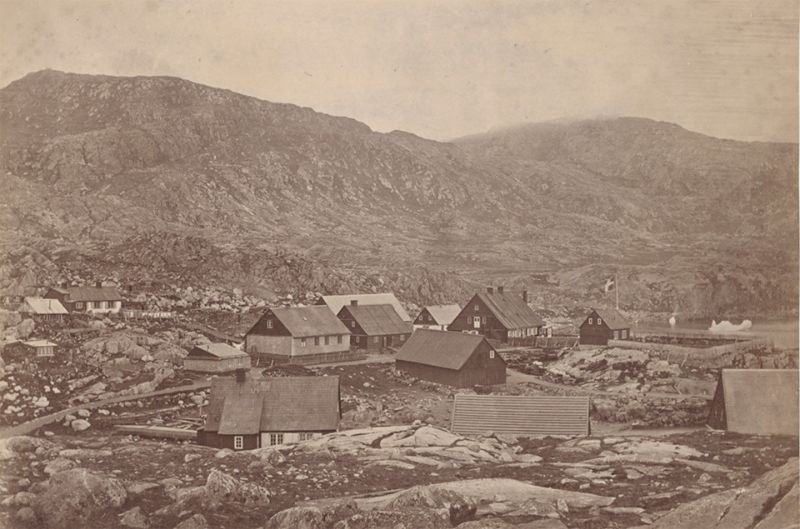

View of Julianeshaab.

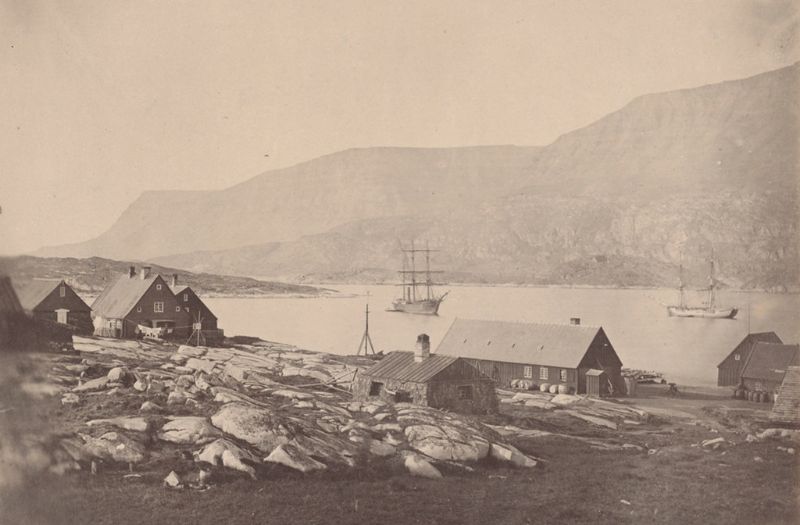

View of settlement and harbour of Godhavn, on the island of Disco.

Young Esquimaux woman, one of the fair dancers.

Dr. Rudolph, his wife, and children.

(Photo credit: William Bradford’s (1823-1892) “Arctic Regions” / Wikimedia Commons).