Poles arrived in Iran (Persia) by the end of 1942.

Following the Soviet invasion of Poland at the onset of World War II in accordance with the Nazi-Soviet Pact against Poland, the Soviet Union acquired over half of the territory of the Second Polish Republic.

Within months, in order to de-Polonize annexed lands, the Soviet NKVD rounded up and deported between 320,000 and 1 million Polish nationals to the eastern parts of the USSR, the Urals, and Siberia. There were four waves of deportations of entire families with children, women, and elderly aboard freight trains from 1940 until 1941.

These civilians included civil servants, local government officials, judges, members of the police force, forest workers, settlers, small farmers, tradesmen, refugees from western Poland, children from summer camps and orphanages, family members of anyone previously arrested, and family members of anyone who escaped abroad or went missing.

Their fate was completely changed in June 1941 when Germany unexpectedly attacked the Soviet Union. In need of as many allies it could find, the Soviets agreed to release all the Polish citizens it held in captivity.

Released in August 1941 from Moscow’s infamous Lubyanka Prison, Polish general Wladyslaw Anders began to mobilize the Polish Armed Forces in the East (commonly known as the Anders Army) to fight against the Nazis.

A Polish woman and her grandchildren in a Red Cross camp in Tehran.

Forming the new Polish Army was not easy, however. Many Polish prisoners of war had died in the labor camps in the Soviet Union. Many of those who survived were very weak from the conditions in the camps and from malnourishment. Because the Soviets were at war with Germany, there was little food or provisions available for the Polish Army.

Thus, following the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941, the Soviets agreed to evacuate part of the Polish formation to Iran. Non-military refugees, mostly women, and children, were also transferred across the Caspian Sea to Iran.

Starting in 1942, the port city of Pahlevi (now known as Anzali) became the main landing point for Polish refugees coming into Iran from the Soviet Union, receiving up to 2,500 refugees per day. General Anders evacuated 74,000 Polish troops, including approximately 41,000 civilians, many of them children, to Iran. In total, over 116,000 refugees were relocated to Iran.

A woman decorates the front yard of her tent with the Polish national eagle.

Despite these difficulties, Iranians openly received the Polish refugees, and the Iranian government facilitated their entry to the country and supplied them with provisions.

Polish schools, cultural and educational organizations, shops, bakeries, businesses, and press were established to make the Poles feel more at home.

The refugees were weakened by two years of maltreatment and starvation, and many suffered from malaria, typhus, fevers, respiratory illnesses, and diseases caused by starvation.

Desperate for food after starving for so long, refugees ate as much as they could, leading to disastrous consequences. Several hundred Poles, mostly children, died shortly after arriving in Iran from acute dysentery caused by overeating

A tent city houses Polish evacuees on the outskirts of Tehran.

Polish children play among the dormitories of a Red Cross camp.

Thousands of the children who came to Iran came from orphanages in the Soviet Union, either because their parents had died or they were separated during deportations from Poland.

Most of these children were eventually sent to live in orphanages in Isfahan, which had an agreeable climate and plentiful resources, allowing the children to recover from the many illnesses they contracted in the poorly managed and supplied orphanages in the Soviet Union.

Between 1942–1945, approximately 2,000 children passed through Isfahan, so many that it was briefly called the “City of Polish Children”. Numerous schools were set up to teach the children the Polish language, math, science, and other standard subjects. In some schools, Persian was also taught, along with both Polish and Iranian history and geography.

Because Iran could not permanently care for the large influx of refugees, other British-colonized countries began receiving Poles from Iran in the summer of 1942.

By 1944, Iran was already emptying of Poles. They were leaving for other camps in places such as Tanganyika, Mexico, India, New Zealand, and Britain.

A Polish woman smiling to the camera.

A Polish girl landscapes the patch of earth in front of her tent. The photographer noted that “the Poles take great pride in the cleanliness of their camp”.

While most signs of Polish life in Iran have faded, a few have remained. As writer Ryszard Antolak noted in Pars Times, “The deepest imprint of the Polish sojourn in Iran can be found in the memoirs and narratives of those who lived through it. The debt and gratitude felt by the exiles towards their host country echoes warmly throughout all literature. The kindness and sympathy of the ordinary Iranian population towards the Poles is everywhere spoken of”.

The Poles took away with them a lasting memory of freedom and friendliness, something most of them would not know again for a very long time.

For few of the evacuees who passed through Iran during these years (1942 -945) would never see their homeland again. By a cruel twist of fate, their political destiny was sealed in Tehran in 1943.

In November of that year, the leaders of Russia, Britain, and the USA met in the Iranian capital to decide the fate of Post-war Europe. During their discussions (which were held in secret), it was decided to assign Poland to the zone of influence of the Soviet Union after the war.

Refugees from Poland on the outskirts of Tehran.

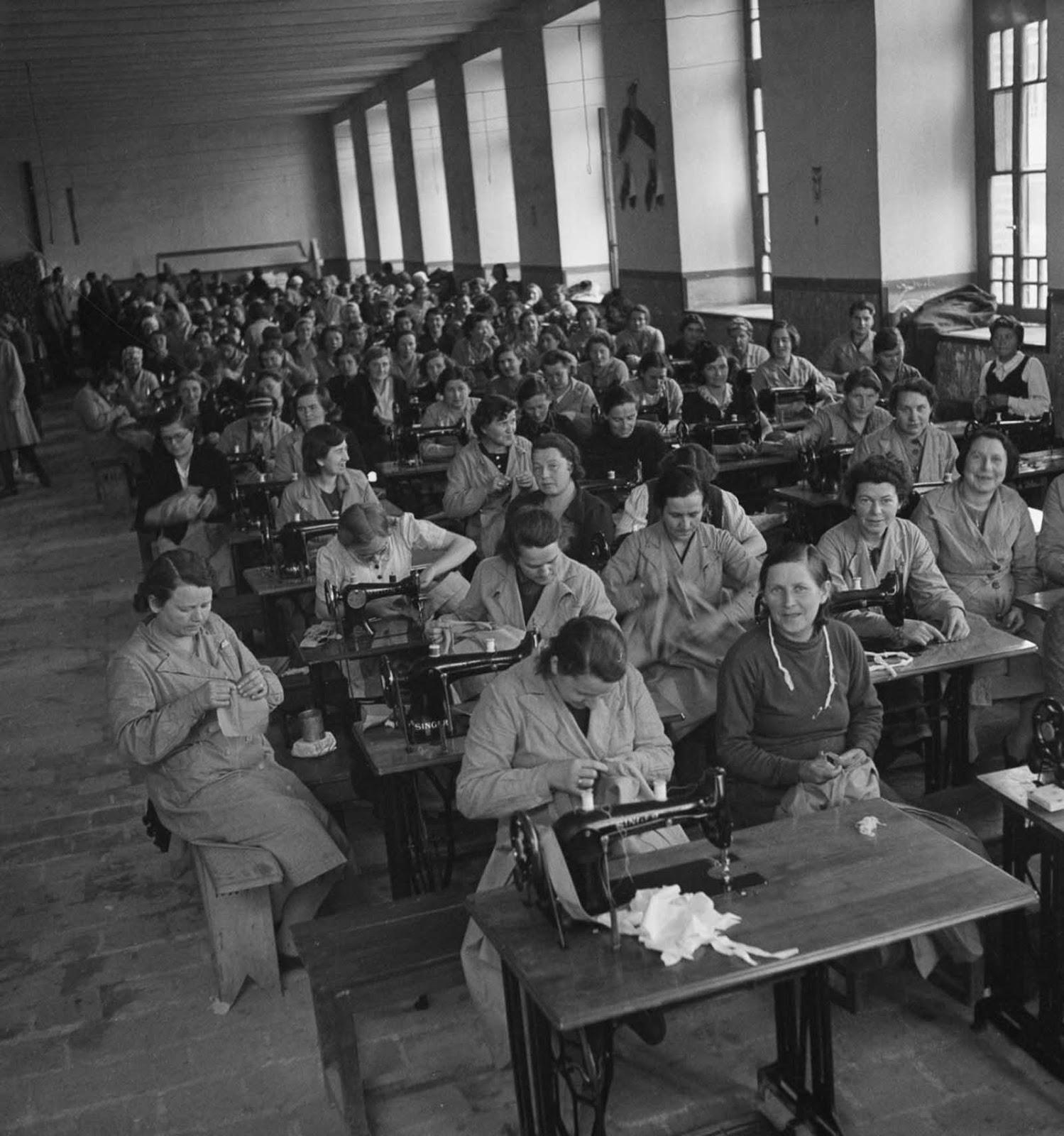

Polish women making their own clothing at a camp in Tehran.

Despite these difficulties, Iranians openly received the Polish refugees, and the Iranian government facilitated their entry to the country and supplied them with provisions.

Thousands of the children who came to Iran came from orphanages in the Soviet Union, either because their parents had died or they were separated during deportations from Poland.

In late 1942 and early 1943, Polish camps in Iran were located at Tehran, Isfahan, Mashhad and Ahvaz.

A Polish woman in Tehran.

A Polish boy carries loaves of bread provided by the Red Cross.

Evacuees wear donated woolen bathrobes as overcoats.

Polish women doing laundry at the camp.

A Polish woman holds her baby girl at an evacuee camp in Tehran.

A Polish refugee who works as a guard at the camp.

A Polish girl wears a heavy sheepskin coat at a refugee camp.

A young Polish refugee does a military salute outside his tent.

(Photo credit: Nick Parrino / Library of Congress).