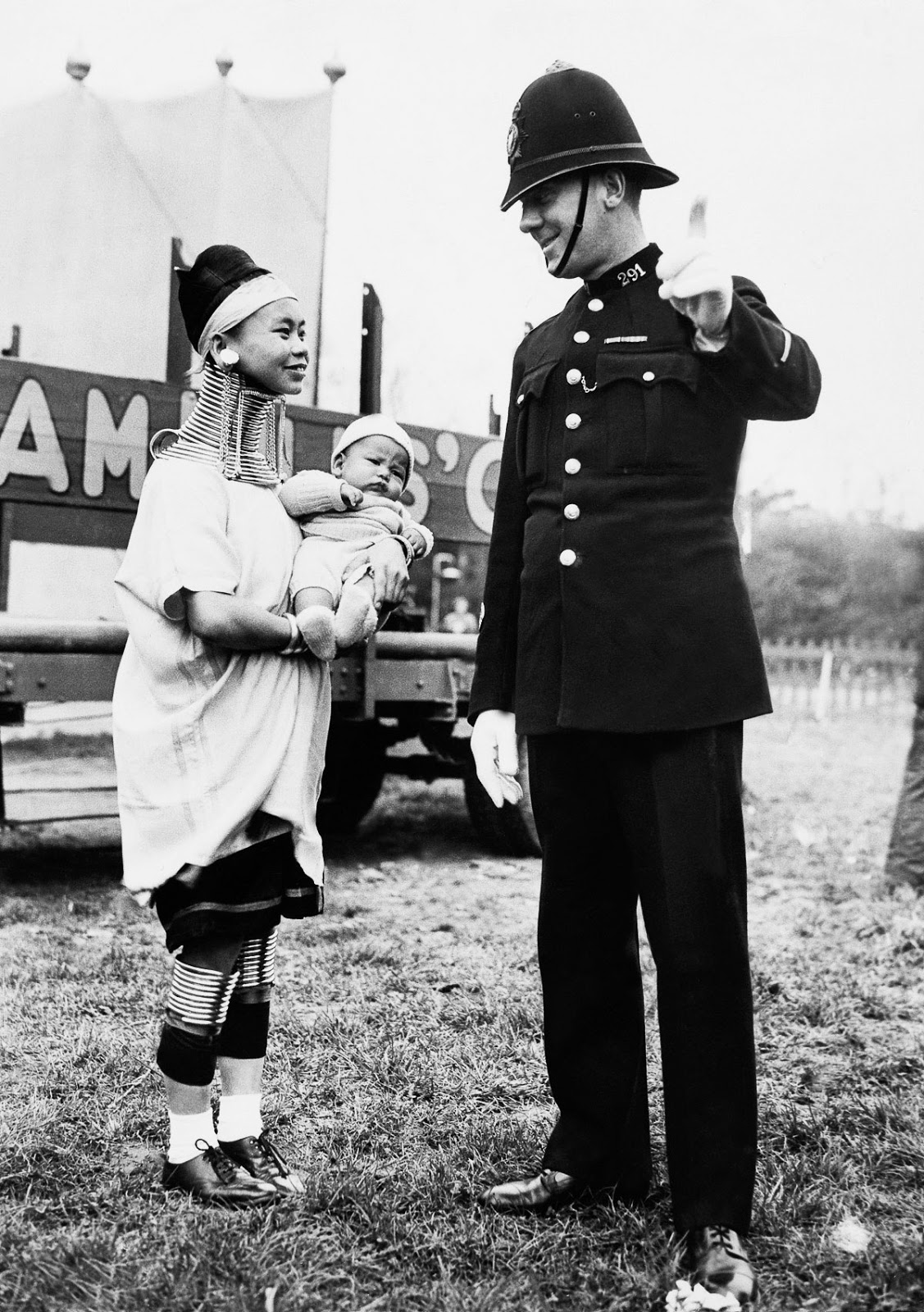

This picture is truly fascinating because we might look at the women for their strange neck elongation traditions but then we see the guard and realize looking from the outside every culture seems strange.

The Kayan Lahwi people, also known as Padaung, are an ethnic group with populations in Myanmar (Burma) and Thailand. Padaung women are well-known for wearing neck rings, brass coils that are placed around the neck, appearing to lengthen it. The women wearing these coils are known as “giraffe women”.

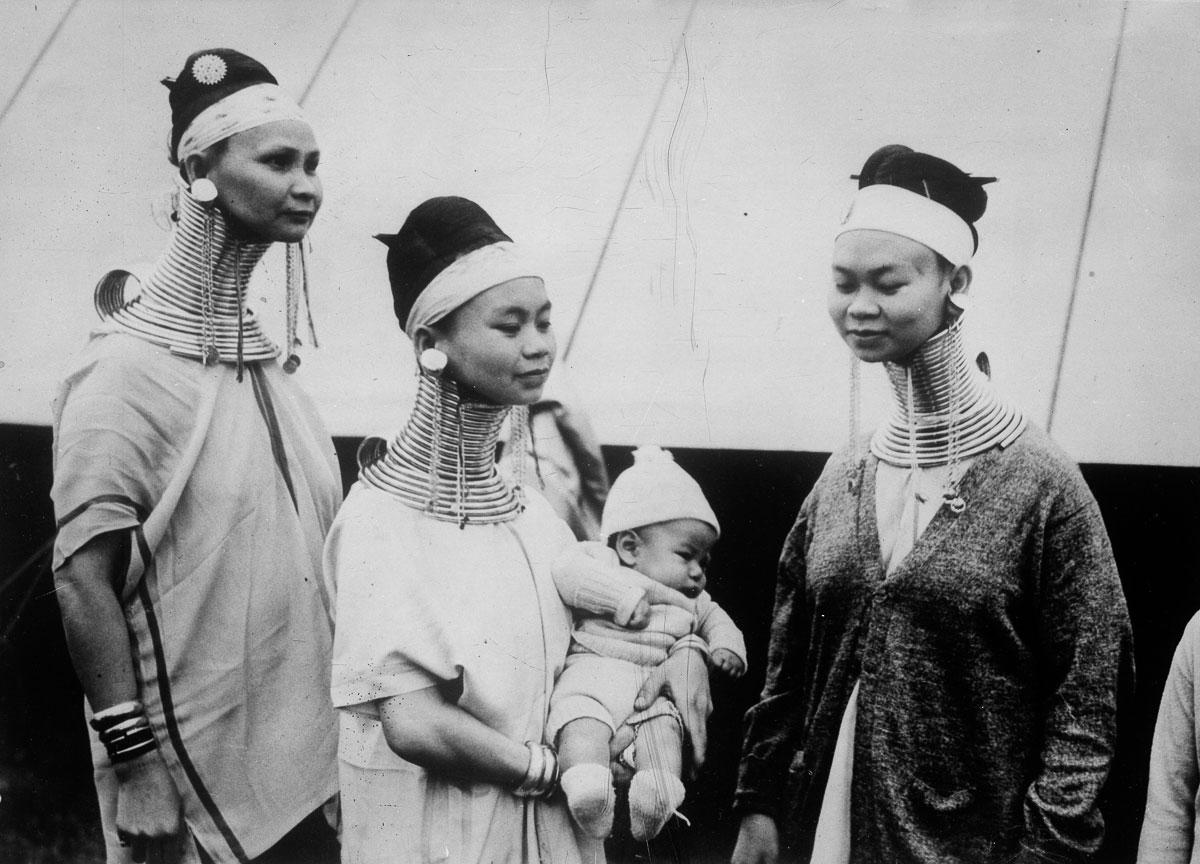

This set of photographs is taken in 1935 when a group of Padaung women visited London. In the 1930s, circuses and shows were extremely popular in the United Kingdom and these women, advertised as “giraffe women”, were star attractions, drawing huge crowds.

In their most distinctive custom, beginning at about five years of age, many Padaung girls have their necks wound with spirals of brass. (In earlier days, copper and gold were used as well.) A bedinsayah (spirit doctor) puts the coils into place on a day determined by divination to be auspicious.

The first spiral, put on a girl at the age of five or so, is usually about four inches high (10 cm); in approximately two years, another coil is added. Coils are then added sporadically until a limit of 21-25 is reached, at the age of marriage.

Padaung women asking a London policeman for directions, 1935

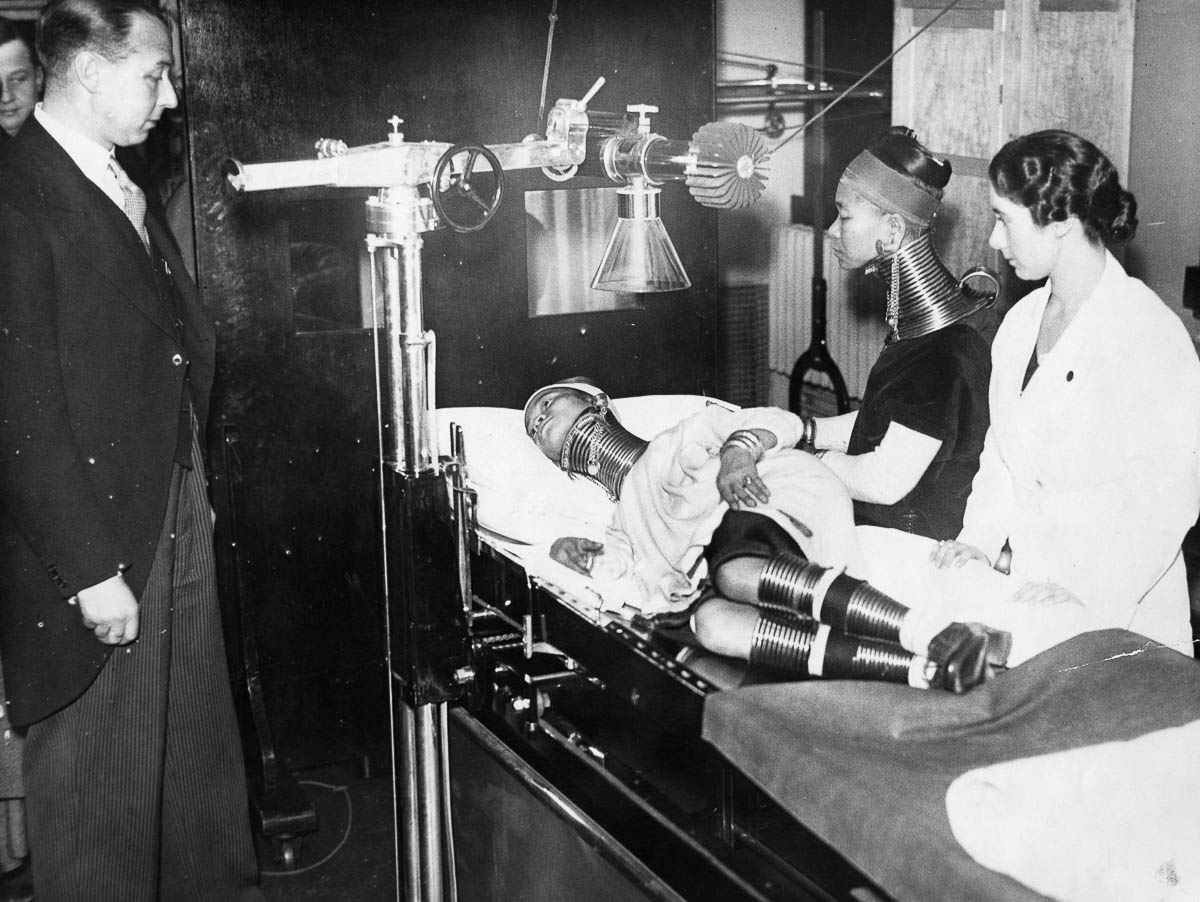

The spiral may reach a foot in height (30 cm) and weigh 20 pounds (9 kg); this gives the illusion of a stretched neck. but the actual effect is that of pushing down the collarbones and rib cage to distort the chest and slope the shoulders. In fact, the weight of the brass pushes the collar bone down and compresses the rib cage.

The neck itself is not lengthened; the appearance of a stretched neck is created by the deformation of the clavicle (chest) and the sloping of the shoulders.

The coil, once on, is seldom removed, as the coiling and uncoiling is a lengthy procedure. It is usually only removed to be replaced by a new or longer coil. The muscles covered by the coil become weakened.

The women wearing these coils are known as “giraffe women”.

The neck itself is not lengthened; the appearance of a stretched neck is created by the deformation of the clavicle.

Waving Londoners upon their arrival at Victoria Station.

Doctors examining a Padaung woman.

One of the women celebrates her 21st birthday with a cake.

Padaung women playing cards.

Many ideas regarding why the coils are worn have been suggested, often formed by visiting anthropologists, who have hypothesized that the rings protected women from becoming slaves by making them less attractive to other tribes.

It has also been theorized that the coils originate from the desire to look more attractive by exaggerating sexual dimorphism, as women have more slender necks than men. It has also been suggested that the coils give the women a resemblance to a dragon, an important figure in Kayan folklore.

The coils might be meant to protect from tiger bites, perhaps literally, but probably symbolically. Kayan women, when asked, acknowledge these ideas and often say that their purpose for wearing the rings is cultural identity (one associated with beauty).

In recent years, many Padaung women began breaking the tradition, though a few older women and some of the younger girls in remote villages continued to wear rings.

In Thailand, the practice has gained popularity in recent years because it draws tourists who bring revenue to the tribe and to the local businessmen who run the villages.